Press release: embargoed to Sunday 24 October 00:01

21 October 2010

RSE calls for Scotland to take urgent and innovative action on broadband.

“Communication is the life blood of society. Scotland’s future depends on having in place an effective digital infrastructure that will underpin a successful economy, vibrant culture and strong communities” explains Professor Michael Fourman, chair of the report ‘Digital Scotland’ that will be published by the Royal Society of Edinburgh on Tuesday 26 November.

“But when it comes to delivering access to high speed broadband, Scotland is falling behind its international competitors, and so will fall behind in all areas in which high quality communication is vital: the economy, health, education, the delivery of public services and social interaction.”

Following consultation with industry players, community groups, regulators and government, Professor Fourman and his team are calling for urgent action at a Scottish level to increase the volume and speed of access to the internet across the country. “Scotland must take the lead in developing its own digital infrastructure. We should not, and cannot, rely on the UK Government to deliver this for us. The Scottish Government and Scotland’s local authorities must work together to drive forward the digital agenda as they are the bodies that hold many of the levers to do so, such as planning regulations, procurement and business rates.”

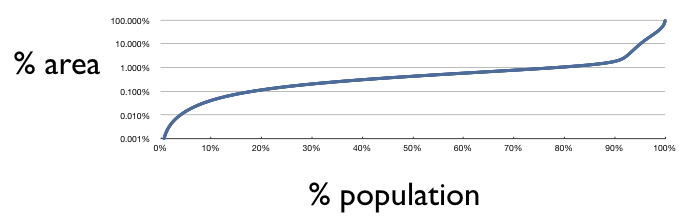

Digital Scotland sets out a comprehensive plan for the creation of a core fibre infrastructure that would bring high speed broadband within reach of all of Scotland’s communities: urban, sub-urban and rural. It calculates the capital cost required to ensure that all of Scotland can keep up with the global pace of development over the next few decades at around £100 million. For reasons of social inclusion and equality of opportunity, Scotland cannot afford a widening digital divide. The report proposes that this enterprise could develop as a distinctively Scottish community effort, bringing benefit to the whole of Scotland, with innovative funding options that need not call on the public purse.

The working group recommends that a Digital Scotland Trust be established to raise finance, procure, operate and maintain the core digital infrastructure in the national interest. It calls for an optic fibre backbone, akin to the trunk roads of our transport network, to be created, that will bring next-generation speeds to a nationwide network of digital hubs from which community networks and service providers can connect to the global internet. And it recognises the need for social hubs, where internet access is available to all, in libraries and other community centres, and where support is available to groups who would otherwise be excluded from digital society.

Geoffrey Boulton, General Secretary of the RSE, comments “As with the industrial revolution two hundred years ago, we are now caught up in another technology-enabled global revolution of possibly similar magnitude. The coupling of new digital technologies that permit acquisition and manipulation of massive amounts of information with devices that put instantaneous communication in the hands of all, is again revolutionising the global economy and social, political and personal relationships. It is a revolution that has not yet run its course. It has both benefits and dangers, and its ultimate trajectory is uncertain. What is not uncertain is the need for Scotland to be at the forefront of this revolution as it was in the 19th century.”

“Good internet access is crucial to our competitiveness in global markets and the survival of our local communities,” Professor Fourman continues, “The pace of chance is likely to quicken rather than falter, which itself will create many challenges because, as recent history has shown, the trajectory of technological development is likely to be unpredictable, as will many of the uses to which it will be put. We are confident, however, that continuing advances in digital technologies will produce further benefits for society.”

Broadband communication offers dramatic increases in economic efficiency through reduction of transaction costs, and the opening of access to global markets. These come hand in hand with advances in data collection and analysis, improved user engagement provides real time customer feedback. Improved decision making reduces the reaction times of businesses in responding to threats and opportunities, claims the report.

And it’s not just about business. The social benefits are enormous – enhanced broadband capacity increases social interaction in communities, opening up more opportunities and greater flexibility at work and in leisure. Both consumers and producers benefit from a more efficient economy. More people have the opportunity to contribute to the workforce. Rural areas excluded from the modern economy can now engage. Parents staying at home to raise children can work flexibly from home.

The web has revolutionised social interactions amongst the young in particular. Social networking sites, pervasive communication and ready access to information and knowledge through instant search are not an integral part of the social structure of modern life. In the USA for example 17% of couples married in the past 3 years first met on an online dating site.

Information technology is also providing a powerful stimulus to the strengthening of civil society, in which many hopes were invested at the time of parliamentary devolution. Digital systems have the capacity to enhance the delivery of public services at a reduced cost in health, education, social services and other areas of government responsibility.

Lack of infrastructure capacity limits the provision of local access, the delivery of next-generation speeds to homes and businesses, and the rollout of mobile data services. The Digital Scotland group welcomes BT’s work to extend its fibre to more exchanges; and the announcement on 20 October that the Highlands and Islands have been successful in securing one of BDUK’s three rural broadband pilot projects which will be delivered in conjunction with the BBC. The important point is to ensure that this delivers open access to affordable backhaul at fibre speeds. These initiatives will reduce the scope and lower the cost of the programme required.

The report is already receiving widespread support.

Influential Scottish businessman Sir Angus Grossart commented “This report should be implemented. It will be a potent lever to liberate and develop the abilities and potential of Scotland, at a low cost. The enhancement of our communications infrastructure will have a transformational effect, across the widest areas of activity and geography.”

David Cairns, Chair of ScotlandIS welcomed the report, explained “A world class communications infrastructure is essential if we are to give Scottish entrepreneurs the ability to address global markets. It is also essential to be internationally competitive in the 21st century. The opportunity is exciting, but if we fail to seize the day we also face the threat of a weakening competitive position because others are not standing still. ScotlandIS welcomes this report which sets out a practical, affordable plan to deliver a future proofed digital infrastructure for all Scotland's communities, businesses and public services.”

Jeremy Peat, BBC Trustee for Scotland, commented “I very much welcome this thoughtful report and wholly agree with the importance of spreading access to high speed broadband across Scotland - and encouraging its take up. I would note, regarding take up, that the reasons for low broadband take up in West Central Scotland also merits attention.”

http://bit.ly/digiscot

http://twitter.com/digiscot

http://digital-scotland.blogspot.com

ENDS

This information and further details/interview arrangements from:

Susan Bishop, RSE

sbishop@royalsoced.org.uk

0131 240 2789

07738 570 315

Or

Carol Anderson

The Business

0131 718 6022

07836 546 256